Kathman-Do, Kathman-Don’t:

Linking Capital of Volunteers after Disaster in Nepal

By Anne Tadgell

Let me tell you a story about the best job I’ve ever had. One and a half hours drive northwest of Kathmandu, I shared a three-story concrete hostel with 70 other people. We sweated through 8 hours of hard labour 6 days a week, moving wheelbarrows and shovels through heavy dirt. Showers were by bucket and meals were eaten from a plate resting in our laps. I had never been happier.

Promoted on the idea that anyone who felt compelled to help disaster-affected communities could show up and be tasked with meaningful work, All Hands Volunteers (now All Hands and Hearts) is an American disaster-response and recovery charity. Volunteers register online, board their flights, and show up to bases across the world with only their backpacks and good intentions. All Hands does not charge volunteers to work with them. Three meals a day and a warm place to sleep are provided. It’s a haven for young, cash-strapped backpackers with a wealth of time and energy.

The Nepal response was my second project with All Hands. One year previously, during my Master’s field work in Manila, I volunteered on the earthquake recovery program in Bohol for 1 month. In those 4 weeks, I reveled in intense physical labour alongside some of the most motivated and generous individuals from around the world. I felt useful, inspired, like I was helping fellow humans get back on their feet after devastation; meeting them where they were and saying ‘we will walk this path together’. And I hoped for a repeat experience in Nepal.

Work hard. Rest hard.

In the first six months of the response, All Hands was focused on clearing and leveling sites with damaged homes around Kathmandu. In search of new beneficiaries with acute needs, the organization opened two new bases in Nuwakot and Sindhupalchowk provinces. I joined just as the Kathmandu base was closing and quickly moved to Nuwakot. Dozens of us piled into a 9-room hostel that we filled with metal bunk beds and thin mattresses. Those seeking more privacy pitched tents in the backyard.

Work quickly piled up. Each morning, teams of 5-6 volunteers walked to a household previously assessed and prioritized by the impartial assessment team based on the severity of their needs (e.g. presence and number of children, level of income, extend of damage to structure, etc). With shovels, sledgehammers and wheelbarrows, we cleared the debris of collapsed homes and leveled the land for future construction. This was a vital first step in the reconstruction process, yet for many beneficiaries, unaffordable. Our quirky, energized, often musical approach to the work intrigued and entertained the locals. We grew accustomed to working with an audience.

Foreign travelers like to seek out creature comforts, and the community adapted to market services for our needs. Eight hours of working in the dirt created a lot of laundry. An entrepreneurial resident of the town noticed this and purchased an electric washer-dryer to remedy our dirt-stained clothes. Local restaurants learned how to cook french fries or omlettes to our taste, and these quickly became our hangouts. The one ‘bar’ in town, a sheet-metal and wood shelter with wooden benches serving the local rice wine ‘raksi’, was a hotspot in the evenings. Local shops stocked up on coveted Dairy Milks and other western snacks to satisfy our cravings. We worked hard, and we rested hard. The money flowed quickly into the town we were working to serve.

Despite the basic living conditions and backbreaking work, the motivation and sense of purpose that the work offered continued to inspire us. Nightly meetings were a time to share news, progress and encouragement. One such meeting, as one long-term volunteer said his goodbyes, he exclaimed that this was the “best job I ever had.” It quickly became our anthem.

Everyone Has Something To Offer

Volunteers and staff who were skilled in construction and engineering (‘skilled’ volunteers) contributed directly to the response and recovering communities. On sites where repair work, demolition, or rebuilding was happening, skilled staff were hired to manage other volunteers. An American construction and demolition expert joined us to train a group of expat volunteers on how to demolish damaged structures safely by hand. Skilled volunteers were rare but valuable.

Capacity building was a priority for the organization. As work transitioned from debris clean up to school building, three engineering apprentices were hired to support the expat Project Managers, providing the apprentices with an entry point and experience in the industry. All Hands also hired local masons, like stonemasons and concrete workers. Some were already skilled and could speed project progress up, while some needed further skill development that was included with their employment. The aim of this initiative was to provide them work and build their capacity in the short term so that they could continue applying those skills long after our programs moved on.

‘Unskilled’ volunteers, or those without construction skills, still brought their own talents and creativity to our work. Those with photography skills and high quality cameras were hired to produce content for social media and the website. Musicians composed songs about their work (I remember a beautiful tune that went “Kathmandu, Kathmandon’t, Kanthmanwill, Kathmanwon’t” which was often sung as volunteers unwound in the evenings). Some knew how to repair tools or could add bamboo infrastructure to the base, like canopies. One of the more culinary-inclined volunteers even built a fire pit and roasted a Christmas pig.

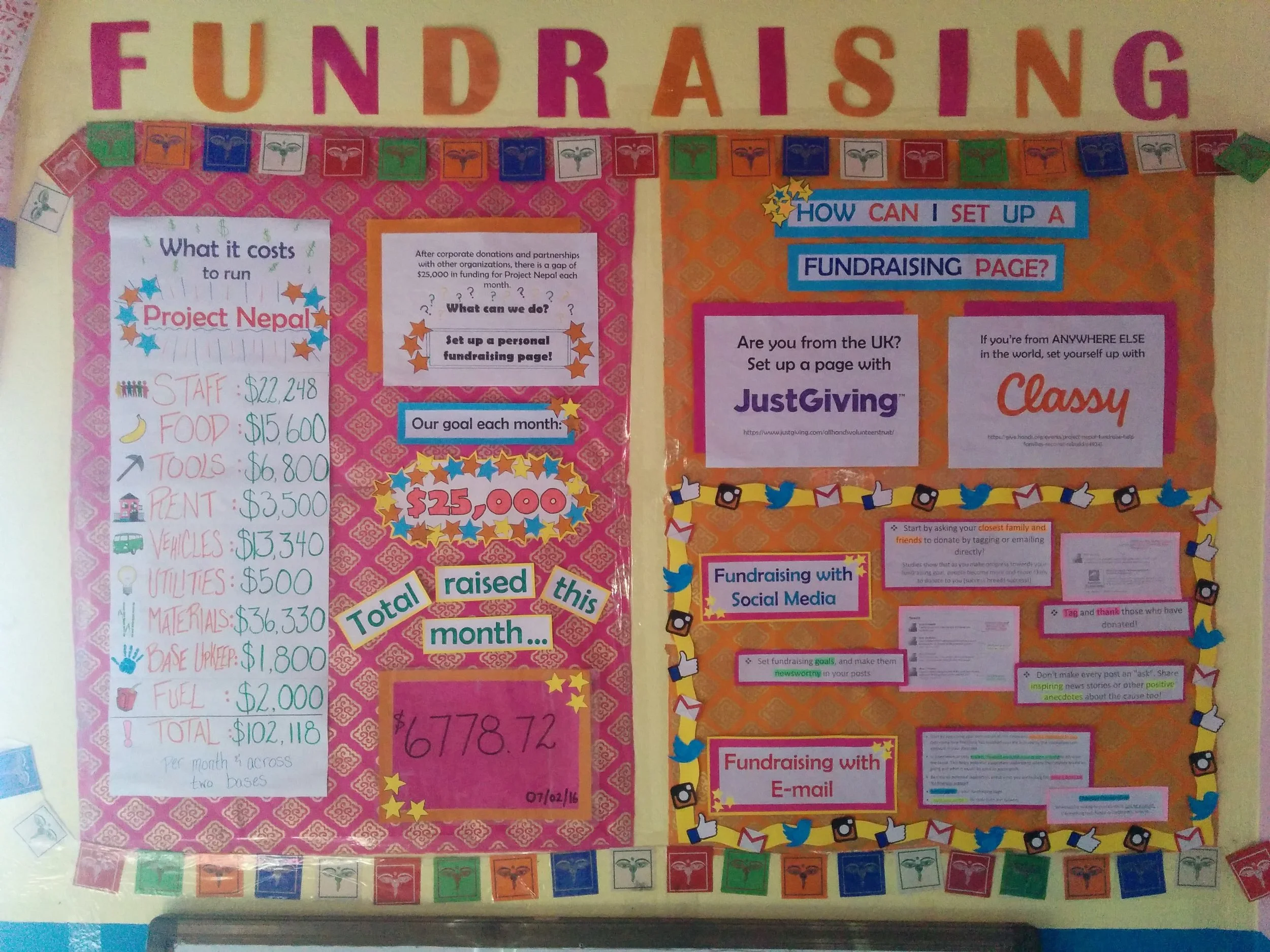

But the greatest value in an unskilled volunteer was their social network – their linking social capital. While All Hands did not charge volunteers to stay or work, it did encourage volunteers to fundraise. Virtually every volunteer had a social media linked to hundreds of friends and families - networks that could be tapped for donations through a few engaging social media posts and hashtags. Engagement Coordinators were hired (myself included) to help volunteers in the art of presenting their work in compelling and actionable ways to those back home. Over time, I felt we had become part aid organization, part business venture.

Shadow work

At some point during my tenure in Nepal, All Hands made the decision to leave the UN OCHA (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs) system that coordinated aid response after disaster. While I have full clarity on their reasoning for doing so, concerns grew amongst some staff and volunteers that the organization was now free to prioritize donor interests as well as community needs for programming. Around the same time, we were looking for larger sites that could accommodate more volunteers (and their linking capital) without needing to move the base. The answer came quickly in the form of schools and school building.

Outside of the work, our presence in the community was having adverse impacts. Seventy plus volunteers flooding a community led to unequal dispersal of income. For example, there were 2 families with washing machines who were receiving our weekly business while other shops watched. The restaurants that adapted to western diets or could cater to large groups were preferred over others. Volunteers had their usual spots and rarely diversified, which may have created or exacerbated income gaps in the community.

As mentioned, we rested as hard as we worked. Often, that rest included alcohol, both imported and local. There were a handful of times when the community came to our base to make noise complaints for the nights prior. Volunteers would play loud music, stay up and out past an 11pm curfew, and loudly trek home from evenings at the bar, disrupting the quiet streets. Our free time activities didn’t always align with the culture of the town.

Meeting whose needs?

All Hands was an organization open to anyone who can afford to travel to disaster areas and volunteer their time. At the time I volunteered, they were providing free labour to hard hit communities and families desperately in need of help and who may not have been able to wait for more bureaucratic systems of aid to step in. Through volunteer- driven work, All Hands was able to move quickly to offer aid, provide a variety of skills both hard and soft, and inject cash into rural communities recovering from disaster. Their programs in Nepal continue today.

But with all the positives, I think it’s important to reflect on how our presence and work may have negatively impacted vulnerable communities as well. When discussing linking capital after disaster we must also be cautious of voluntourism, in this case the presence of middle class, often white volunteers arriving in less developed, disaster-affected countries with minimal relevant skills and charging ahead with projects developed outside the UN/OCHA system. Could our valuable linking capital have been better or differently employed to support Nepal’s recovery?

“Best job I ever had”? Sure. But it shouldn’t be about me. Best aid ever provided? Critical needs met after a disaster? Most sustainable recovery and development strategies applied? Questions I still ask myself today.